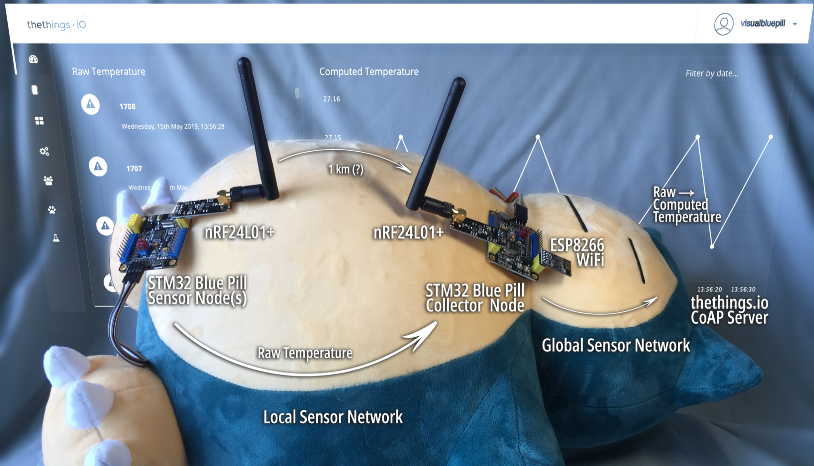

Mythical sonorous creature for belly illustration purpose only. Not required for implementation. Do not attempt to catch!

Build Your IoT Sensor Network — STM32 Blue Pill + nRF24L01 + ESP8266 + Apache Mynewt + thethings.io

Law of Thermospatiality: Air-conditioning always feels too warm AND too cold by different individuals in a sizeable room

Law of Thermospatiality in action

It’s impossible to get perfect air-conditioning in any room… But we can try! We begin by installing 5 temperature sensors around our living room (to monitor the actual temperature at 5 different spots).

We’ll call them the 5 Sensor Nodes. Each Sensor Node will be an STM32 Blue Pill with a temperature sensor.

Running cables through the living room is out of the question, so our Blue Pills will have to connect wirelessly to transmit the temperature data. Perhaps with an ESP8266 WiFi module?

But each Sensor Node is only doing a dead simple job… 1️⃣ Read the temperature sensor 2️⃣ Transmit the temperature value. Do we really need an ESP8266 with the whole CoAP + UDP + IP stack? (Don’t forget: we need to configure each ESP8266 with WiFi MAC Address security in case somebody spoofs our Sensor Nodes and breaks into our home WiFi)

The Nordic Semiconductor nRF24L01 wireless transceiver is perfect for this scenario. Each Blue Pill transmits the temperature data via the nRF24L01 module to a simple 2.4 GHz Sensor Network, without any WiFi / IP / UDP protocol overheads.

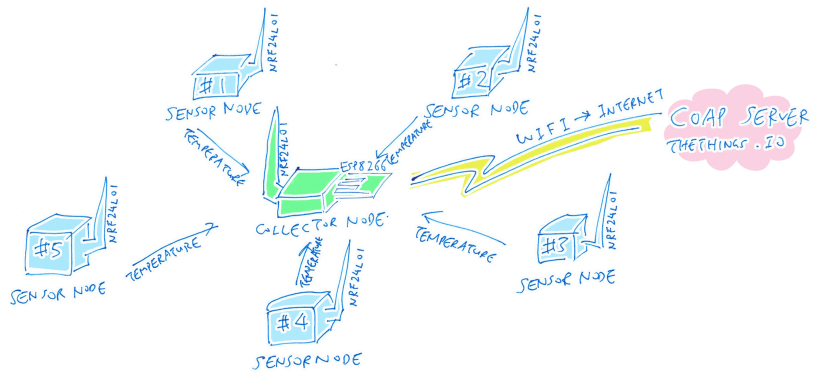

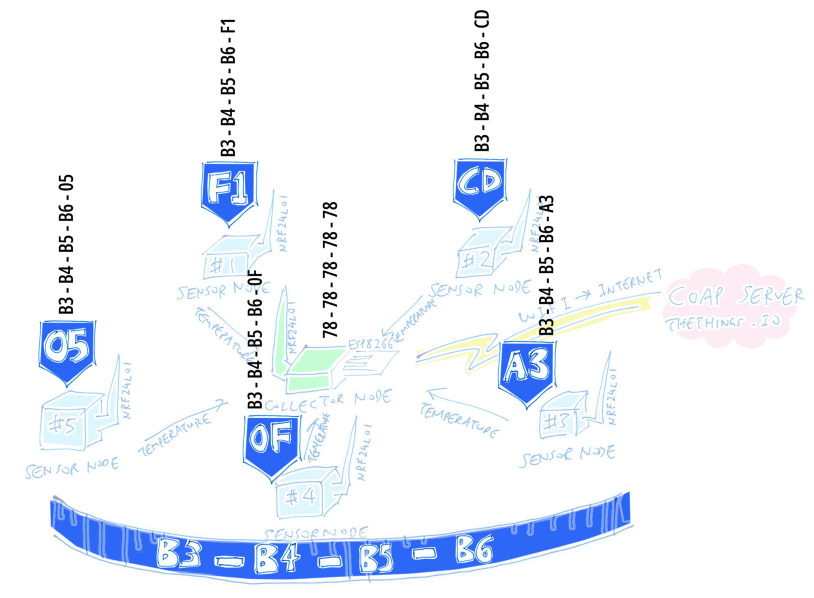

To bridge the 5 Sensor Nodes to a proper IoT CoAP Server (like thethings.io), we use a Blue Pill running as a Collector Node. It collects temperature data from Sensor Nodes via nRF24L01, and transmits the data to the CoAP Server. That way, only ONE node needs the ESP8266 and the entire CoAP + UDP + IP stack (and the WiFi security).

Our Sensor Network: 5 Sensor Nodes (nRF24L01) and 1 Collector Node (nRF24L01 + ESP8266 WiFi)

With this Sensor Network design, we keep the Sensor Nodes dead simple, and push the complex embedded software to the Collector Node, for easier troubleshooting and upgrading. If we upgrade to the nRF24L01+ with RF power amplifier, the Sensor Nodes can be as far as 1 kilometre away from the Collector Node! (Subject to various conditions of course)

In this tutorial we’ll learn to set up this Sensor Network (refer to the diagram)…

1️⃣ One Blue Pill shall serve as the Sensor Node. Via the nRF24L01 network, the Sensor Node transmits the Temperature Sensor value every 10 seconds to another Blue Pill, the Collector Node.

2️⃣ Another Blue Pill shall serve as the Collector Node. Via the nRF24L01 network, the Collector Node shall receive the Temperature Sensor value from the Sensor Node.

3️⃣ Via the ESP8266 WiFi network, the Collector Node shall transmit the Temperature Sensor value to the CoAP Server at thethings.io. So that the sensor data may be transformed, recorded and visualised at thethings.io.

By the end of the tutorial, we’ll have a Sensor Network like this running on two Blue Pills with nRF24L01 and ESP8266…

Demo of Sensor Network with two Blue Pills with nRF24L01 and ESP8266

💎 Sections marked with a diamond are meant for advanced developers. If you’re new to embedded programming, you may skip these sections

Connect the Hardware

We’ll need the following hardware for one Collector Node and one Sensor Node…

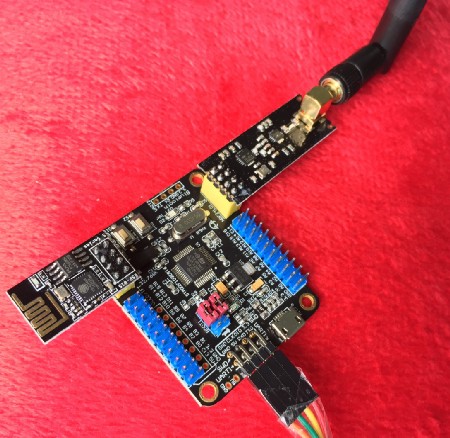

1️⃣ Two Blue Pills, or two Super Blue Pills which have onboard connectors for ESP8266 and nRF24L01…

2️⃣ Two ST-Link V2 USB Adapters (or compatible) for connecting the (Super) Blue Pills to your computers. Check the previous article for the instructions on connecting the (Super) Blue Pills to ST-Link V2. (Look for the ST-Link V2 photo)

3️⃣ Two Computers (Windows 10 or macOS) for debugging the two (Super) Blue Pills

4️⃣ One ESP8266 WiFi module. I tested with the ESP-01S.

5️⃣ Two nRF24L01 RF modules. I used the nRF24L01+, which includes an RF power amplifier for longer range (up to 1 km).

Super Blue Pill with ESP8266 (left) and nRF24L01 (right)

If you have two Super Blue Pills…

Collector Node: Plug both ESP8266 and nRF24L01 modules into the onboard connectors of a Super Blue Pill.

Sensor Node: Plug the nRF24L01 module into the onboard connector of the other Super Blue Pill.

Connect Blue Pill to ESP8266

Connect Blue Pill to nRF24L01

If you have two older Blue Pills…

Collector Node: Using a breadboard, connect a Blue Pill to the ESP8266 and nRF24L01 modules as shown.

Sensor Node: Using a breadboard, connect the other Blue Pill to the nRF24L01 module as shown.

Download, Configure, Build and Run

On both computers, follow the instructions in the previous tutorial under the sections below to download, configure, build and run the Blue Pill application…

1️⃣ Section “Download Source Code” of the

previous tutorial. If you have previously downloaded stm32bluepill-mynewt-sensor, rename

the old folder before downloading.

2️⃣ Section “Configure WiFi Settings” of the previous tutorial

3️⃣ Section “Build The Application” of the previous tutorial

4️⃣ Section “Run The Application” of the previous tutorial

When the Collector Node and Sensor Node are communicating correctly, you should see messages like these…

1️⃣ Sample log for Collector Node

2️⃣ Sample log for Sensor Node

However the Collector and Sensor Nodes won’t operate correctly yet… There’s a list of Hardware IDs that you need to populate in the settings file, due to the way network addresses are allocated in nRF24L01 networks. Read on to learn more…

Sensor Network Addresses

Unlike complicated WiFi networks that dynamically allocate IP addresses, nRF24L01 networks are so simple that we need to allocate the addresses ourselves.

How does the Collector Node know which Sensor Node sent the temperature data? Each Sensor Node is distinguished from the other 4 Sensor Nodes by an 8-bit address that we allocate to each Sensor Node. For the demo we’re using these addresses (in hexadecimal) for the 5 Sensor Nodes (derived from the sample configuration in the datasheet)…

Sensor Node Addresses (last byte): F1, CD, A3, 0F and 05

💎 nRF24L01 operates in the crowded licence-free 2.4 GHz frequency band (shared with WiFi, Bluetooth and microwave ovens). The above 5 bytes, which contain as many different bits as possible, were chosen so that we could detect (and reject) packet addresses that have been corrupted due to RF interference.

What if our neighbour decides to set up their own nRF24L01 Sensor Network? To prevent address collisions, we distinguish each Sensor Network by allocating a unique 32-bit (4-byte) network address. For the demo we’re using this network address…

Sensor Network Address (four bytes): B3-B4-B5-B6

When we combine the Sensor Network Address with the Sensor Node Address, we get 5 unique node address, each containing 5 bytes…

Sensor Node 1 Full Address: B3-B4-B5-B6-F1

Sensor Node 2 Full Address: B3-B4-B5-B6-CD

Sensor Node 3 Full Address: B3-B4-B5-B6-A3

Sensor Node 4 Full Address: B3-B4-B5-B6-0F

Sensor Node 5 Full Address: B3-B4-B5-B6-05

Which we may interpret as the 5 statically-allocated “IP Addresses” for each Sensor Node in our nRF24L01 network.

Collector and Sensor Node Addresses

What about the Collector Node? We’re free to allocate any unique 5-byte node address. (No need to share the same 4 bytes of the Sensor Network Address as the other nodes) For the demo, we’re using…

Collector Node Address (five bytes): 78-78-78-78-78

nRF24L01 Settings. From https://github.com/lupyuen/stm32bluepill-mynewt-sensor/blob/master/targets/bluepill_my_sensor/syscfg.yml#L66-L91

If you need to configure the

nRF24L01 addresses to avoid conflicts with nearby nRF24L01 networks, edit the settings in targets/bluepill_my_sensor/syscfg.yml

Assigning Network Addresses Automatically

Each Sensor Network can have 1 Collector Node and up to 5 Sensor Nodes. So we may need to assign 6 addresses manually to each of the 6 nodes. Does this mean we need to create 6 different ROM images for flashing, each with a different address inside? Nope, there’s an easier way!

Inside every Blue Pill is a unique 12-byte Hardware ID that’s burned in during manufacturing. I have provided a Sensor Network Library that…

1️⃣ Reads the Blue Pill’s Hardware

ID (by calling Mynewt’s hal_bsp_hw_id()

API)

2️⃣ Matches the Hardware ID against a configurable list of Hardware IDs for the Collector and Sensor Nodes

3️⃣ And assigns the respective addresses for the Collector and Sensor Nodes.

Hardware ID settings. From https://github.com/lupyuen/stm32bluepill-mynewt-sensor/blob/master/targets/bluepill_my_sensor/syscfg.yml#L44-L65

All you need to do is to fill in

the list of Hardware IDs for your Blue Pills in targets/bluepill_my_sensor/syscfg.yml…

To discover the Hardware ID for your Blue Pill, start the debugger and watch out for this message at startup…

NET hwid 57 ff 6a 06 78 78 54 50 49 29 24 67

When updating the settings, convert the Hardware ID into a hexadecimal list like this…

0x57, 0xff, 0x6a, 0x06, 0x78, 0x78, 0x54, 0x50, 0x49, 0x29, 0x24, 0x67

Rebuild the application and restart the debugger. At startup, watch for one of these messages that indicates the type of node…

NET collector node

NET sensor node #1

If you see NET standalone node it means that the program was unable to match your Hardware

ID with any Collector or Sensor Hardware IDs. Verify the list of Hardware IDs in targets/bluepill_my_sensor/syscfg.yml

So only ONE version of the ROM image (containing all 6 Hardware IDs and node addresses) needs to be flashed to all 6 Blue Pills. So easy to deploy and upgrade. The rest happens automatically… like magic!

💎 When we build only one ROM image for all Collector and Sensor Nodes, it means that the same code is present on ALL nodes. Depending on the Hardware ID, some parts of the code are disabled at runtime. This also means that we need to squeeze all code into the 64 KB ROM limit. More about this in a while…

Mynewt Driver for Remote Sensors

Calling Mynewt’s Sensor Framework to poll a sensor. From https://github.com/lupyuen/stm32bluepill-mynewt-sensor/blob/master/apps/my_sensor_app/src/listen_sensor.c#L46-L76

Mynewt has an excellent Sensor Framework that’s perfect for integrating IoT devices with sensors.

No need to code our own background task to poll the sensor periodically (like our temperature sensor) and to process the sensor data… Just tell the Sensor Framework which sensor to poll and how often!

Mynewt triggers our Listener Function to process the sensor data that has been polled.

But our new Sensor Network is complicated. On the Collector Node, Mynewt is blissfully unaware about the Sensor Nodes that are periodically transmitting sensor data to the Collector Node. Can we tell Mynewt about the Sensor Nodes and their attached sensors?

Declaring a Remote Sensor Type for the Raw Temperature Sensor. From https://github.com/lupyuen/stm32bluepill-mynewt-sensor/blob/master/targets/bluepill_my_sensor/syscfg.yml#L135-L155

Yes, with the Remote Sensor Driver that I have provided! When installed on the Collector Node, the Remote Sensor Driver enables Sensor Nodes (and attached sensors) to masquerade as locally-attached sensors!

The above Remote

Sensor Configuration tells Mynewt about a Raw Temperature

Sensor Type that’s attached to a Sensor Node (targets/bluepill_my_sensor/syscfg.yml)…

1️⃣ temp_raw is the name of the Raw

Temperature Sensor Type. This is an integer value (0 to 4095) that’s provided by the Blue Pill Internal Temperature

Sensor (described

in my previous article).

2️⃣ t is the field name that appears in

the message transmitted by the Sensor Node. The message looks like { "t": 1745 }

3️⃣ strd is the union type that shall store the sensor value in memory. This follows

Mynewt’s Sensor Framework convention of using a union to store each type of sensor

value. strd is defined in libs/custom_sensor/include/custom_sensor/custom_sensor.h

4️⃣ AMBIENT_TEMPERATURE_RAW is the unique

Sensor Type ID for the Raw Temperature Sensor Type. Mynewt’s Sensor Framework uses the Sensor Type ID to discover

which Sensor Drivers can return values of each Sensor Type. AMBIENT_TEMPERATURE_RAW is defined in libs/custom_sensor/include/custom_sensor/custom_sensor.h

5️⃣ The last 2 settings declare

whether the sensor provides integer (INT) or double-precision

floating-point (DOUBLE) sensor

values.

Starting the Remote Sensor Listeners. From https://github.com/lupyuen/stm32bluepill-mynewt-sensor/blob/master/apps/my_sensor_app/src/listen_sensor.c#L77-L108

Once we declare the Remote Sensor Type for the remote temperature sensor (and start the Remote Sensor Listeners), we may program the sensor as though it were a local temperature sensor… Mynewt’s familiar Sensor Framework works exactly the same way!

Just provide a Listener Function and Mynewt will helpfully trigger the function whenever it receives sensor data from the Sensor Nodes.

Programming with Distributed IoT sensors becomes fun and easy, with this simple Remote Sensor Driver for Mynewt that converts a Remote Sensor into a Local Sensor. Now we understand why we adopted a multitasking realtime operating system like Mynewt… because without Mynewt, the Collector Node can’t possibly receive and send sensor messages over two different networks simultaneously.

Packaging and shipping Sensor Data

Remember earlier we declared that Sensor Nodes should be kept dead simple, using a simple network (nRF24L01) and a simple deployment method (only ONE ROM image!) The Sensor Data needs to be kept simple too…

1️⃣ Eliminate all floating-point code: On Blue Pill, we pay a hefty price for any computation involving floating-point (decimal) numbers. Even calculating a simple temperature like “28.9 degrees Celsius” will require a huge chunk of floating-point code (from the standard math library) to be embedded in ROM. Which inflates the ROM size, bloating beyond the 64 KB limit.

In this demo we transmit the raw temperature values as integers (directly from Blue Pill’s Analogue-to-Digital Converter) instead of the computed floating-point temperature values (like in the previous tutorial). The integer sensor values are transmitted from the Sensor Node to the Collector Node, and also from the Collector Node to the CoAP Server.

The raw temperature values are converted into floating-point

only upon reaching the CoAP Server at thethings.io. So that we could visualise the temperature

properly as “28.9 degrees Celsius” instead of 1745.

No more floating-point bloat in our ROM!

2️⃣ Compact CBOR encoding instead of JSON: Our Collector Node transmits the raw temperature to the CoAP Server with JSON encoding, which is accepted by all CoAP Servers…

{ "t": 1745 }

During the JSON transmission we

preserve the sensor field name "t" so that it’s easier

to visualise the sensor data and execute rules on the CoAP Server (like thethings.io).

But JSON bloats our sensor data messages — we need 10 data bytes to transmit the simple message above. Hence our Sensor Network demo uses CBOR encoding, a compressed, binary version of JSON. And it’s natively supported by Mynewt.

Between the Sensor Node and the Collector Node, we encode sensor data messages in CBOR format instead of JSON. Which requires only 6 data bytes instead of 10 bytes for the above example!

By adopting CBOR as the message

format in the local Sensor Network, we also simplify the design of the Remote Sensor Driver. The

driver only needs to decode incoming CBOR messages,

and trigger the right Listener

Function. The Remote Sensor Driver selects the Listener Function

based on the sensor field name "t"

💎 Mynewt natively encodes CoAP messages using CBOR encoding. We discard the CoAP Header, keeping only the CoAP Payload in CBOR, which occupies 6 data bytes. An additional byte

0xffis added by Mynewt as the payload terminator. The final byte of the nRF24L01 message is the message counter, useful for detecting missing messages.nRF24L01 messages can be up to 32 bytes in length. But for the demo we have fixed the message length as 12 bytes. It’s big enough to transmit 2 sensor values, yet small enough to reduce the risk of RF interference and allow farther transmission distances. To change the message length, edit the

NRF24L01_TX_SIZEsetting intargets/bluepill_my_sensor/syscfg.yml

Selecting JSON or CBOR Encoding

Now that we have two formats for encoding sensor data…

1️⃣ CBOR Encoding from Sensor Node to Collector Node (via nRF24L01)

2️⃣ JSON Encoding from Collector Node to CoAP Server (via ESP8266)

Does this make Blue Pill device programming twice as difficult?

Not at all! The Sensor Network Library hides the encoding details inside high-level functions that we may call to compose and transmit messages…

0️⃣ Previously we called init_sensor_post() … do_sensor_post()

to send CoAP messages to the CoAP Server via the ESP8266 Network Transport (from the ESP8266 Network

Driver)

1️⃣ Now we call init_collector_post() … do_collector_post()

to send messages to the Collector Node via the nRF24L01 Network Transport

(from the nRF24L01 Network Driver)

2️⃣ And we call init_server_post() … do_server_post()

to send messages to the CoAP Server via the ESP8266 Network Transport

(from the ESP8266 Network Driver)

The nRF24L01

Network Driver was ported from mbed to Mynewt.

The driver settings may be found in targets/bluepill_my_sensor/syscfg.yml

The nRF24L01 driver is connected

to the SPI port and supports simple transmit and receive

functions. There’s no need to call the nRF24L01 functions directly — the Sensor Network Library

calls them when do_collector_post() is invoked.

The nRF24L01 driver handles interrupts raised by the nRF24L01 module when data has been received (so no polling is needed). The driver calls the Receive Callback Function provided by the Remote Sensor Library. The callback function decodes the CBOR message and forwards it to the Remote Sensor Listener Function.

The ESP8266 Network Driver is connected to the UART port. It has been covered in detail in the previous tutorial.

Using CP macros to compose messages for Collector Node and CoAP Server. From https://github.com/lupyuen/stm32bluepill-mynewt-sensor/blob/master/apps/my_sensor_app/src/send_coap.c#L182-L222

Composing messages with the

macros CP_ITEM_STR(), CP_ITEM_FLOAT(), … works

exactly like before. The right encoding (CBOR or JSON) is automatically selected when we call init_collector_post()

and init_server_post()

To allow easier passing and

encoding of Sensor Values, we have created a sensor_value struct

that contains one Sensor Key (e.g. "t" for raw

temperature) and one Sensor Value (int or float). New macros have been created to add a sensor_value to a message: CP_SET_INT_VAL(), CP_SET_FLOAT_VAL(), CP_ITEM_INT_VAL(), CP_ITEM_FLOAT_VAL().

The new macros are used in apps/my_sensor_app/src/send_coap.c

to compose Collector Node messages and CoAP Server messages. All

macros have been updated to support both CBOR and JSON

encoding, selected at runtime (instead of compile-time).

The Sensor Network Library brings us one step closer to the vision of Network-Agnostic IoT… Doesn’t matter whether our devices are connected via ESP8266 or nRF24L01, the same code still works! The Sensor Network Library…

1️⃣ Assigns network addresses (nRF24L01) based on one common ROM image

2️⃣ Provides

generic functions to perform operations on network interfaces, like do_collector_post()

and do_server_post()

3️⃣ Selects message encoding (CBOR or JSON) based on the destination of the message (Collector Node vs CoAP Server)

4️⃣ Enforces a standard data format (CoAP JSON) for aggregating and encoding sensor data when transmitting sensor data to the IoT Server for processing

We’ll now learn how thethings.io may be used to process the standardised sensor data.

💎 The Sensor Network Library is clearly able to transmit sensor data locally (nRF24L01) and over internet (ESP8266)… yet the library has no dependencies on the nRF24L01 and ESP8266 drivers! This was done with a programming trick known as “Inversion of Control” — the network drivers register themselves with the Sensor Network library, not the other way around.

This enables the Sensor Network Library to be truly Network Agnostic. The Sensor Network Library will support many other network adapters and network protocols in future: NB-IoT, LoRa, Sigfox, Zigbee, Bluetooth, …

Configuring the CoAP Server at thethings.io

thethings.io is an excellent example of a modern hosted IoT server that’s capable of processing the CoAP standard-based sensor data transmitted by our Collector Node. Follow the steps below to configure the CoAP Server at thethings.io and understand how the server can transform our sensor data (Raw Temperature to Computed Temperature) and visualise the data…

1️⃣ Follow the video below to

sign up for a 14-day free trial account (no credit card needed) and to install three custom JavaScript

programs for processing the data: forward_geolocate, transform, update_state. The

scripts are located here: https://github.com/lupyuen/thethingsio-wifi-geolocation

Click CC to view the instructions…

💎 If you will be using WiFi Geolocation, copy the script

geolocate.jsand install it as the Cloud Code Function namedgeolocate

2️⃣ The second video explains the steps for creating a dashboard that visualises the Raw Temperature transmitted by our Collector Node.

Click CC to view the instructions…

3️⃣ In the final video we verify

that the Raw Temperature t is transformed to Computed

Temperature tmp correctly. We visualise the Computed Temperature

tmp in the dashboard.

Click CC to view the instructions…

After configuring the demo in thethings.io, we now fully appreciate how a comprehensive end-to-end IoT solution may benefit us…

1️⃣ Gather raw sensor data efficiently from Sensor Nodes dispersed around a region, up to 1 km away

2️⃣ Aggregate and transmit the raw sensor data to a standards-based IoT server (like thethings.io)

3️⃣ Transform the raw sensor data to the final display format (e.g. degrees Celsius) at the IoT server

4️⃣ Visualise the transformed sensor data as realtime text and graphical displays

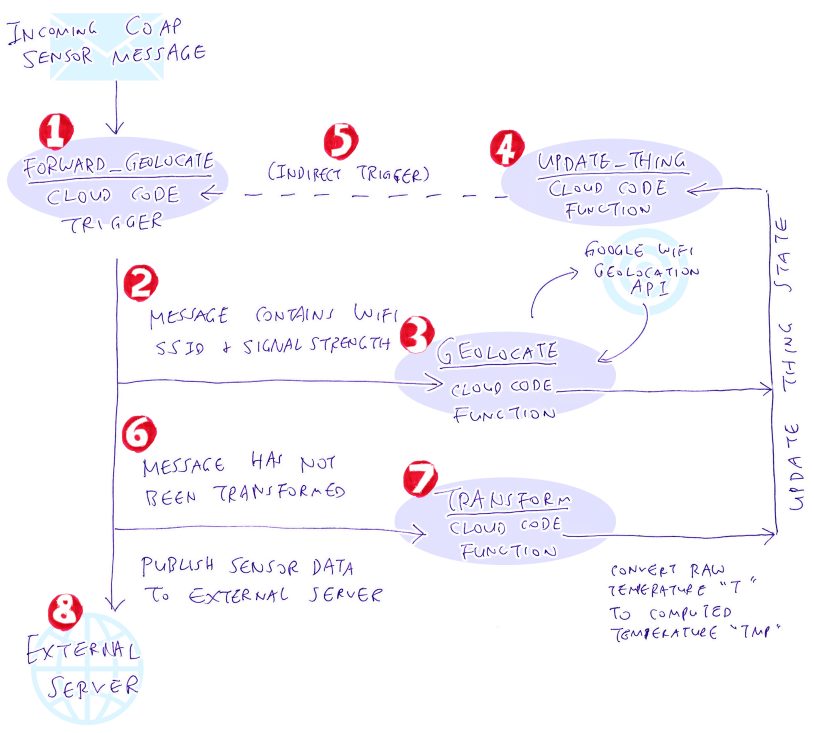

thethings.io Cloud Code Trigger and Functions used in the demo

Processing Sensor Data at thethings.io

With Network-Agnostic IoT, our Collector Node aggregates and transmits sensor data to the IoT Server in a standard format: CoAP JSON. This ensures that our sensor data can be easily processed, regardless of the network and server used. Here’s how we process the sensor data with the CoAP Server hosted at thethings.io…

forward_geolocate, geolocate, transform and update_thing are the Cloud Code

Trigger and Functions that we install at thethings.io to process the sensor data. They call one

another like a Finite State Machine to perform WiFi geolocation, transform sensor values (raw

temperature to computed temperature) and update the thing state…

forward_geolocate Cloud Code Trigger. From https://github.com/lupyuen/thethingsio-wifi-geolocation/blob/master/forward_geolocate.js#L61-L122

1️⃣ forward_geolocate

is the Cloud Code Trigger that will receive any sensor data transmitted by our Collector Node over

CoAP. This trigger allows us to intercept the sensor values and transform them.

2️⃣ forward_geolocate checks whether the message contains any ssid or rssi (signal strength)

fields.

If the ssid and rssi fields were

found, it forwards the message to the Cloud Code Function geolocate for processing.

This was the code from the

previous tutorial that performs WiFi Geolocation given a list of WiFi SSIDs their Signal

Strength. geolocate is not needed if you don’t use the WiFi

Geolocation feature.

geolocate Cloud Code Function. From https://github.com/lupyuen/thethingsio-wifi-geolocation/blob/master/geolocate.js#L66-L114

3️⃣ If WiFi Geolocation is

enabled, Cloud Code Function geolocate

passes the WiFi SSID and Signal Strength info to the Google WiFi Geolocation API. This info was

obtained from the ESP8266 scanning nearby WiFI networks.

The Geolocation API estimates the location of the device and returns the latitude, longitude and accuracy (in metres).

geolocate calls the Cloud Code Function update_thing to update the thing state with the geolocation results,

so that the results will be stored in thethings.io and the dashboards will be updated.

update_thing Cloud Code Function. From https://github.com/lupyuen/thethingsio-wifi-geolocation/blob/master/update_thing.js#L5-L49

4️⃣ Cloud Function update_thing

receives the updated sensor values (latitude, longitude, accuracy) and updates the thethings.io thing

state by calling the HTTP API.

Since the option broadcast=true was specified, all the dashboards for the thing will

be instantly refreshed, including the geolocation result.

5️⃣ The updating of the thing

state also indirectly triggers forward_geolocate with the

updated sensor values. Which leads to the next step…

forward_geolocate Cloud Code Trigger. From https://github.com/lupyuen/thethingsio-wifi-geolocation/blob/master/forward_geolocate.js#L61-L122

6️⃣ The next step of forward_geolocate

checks whether the sensor values have been transformed (i.e. whether the transformed key exists).

If the values have not been

transformed, it calls Cloud Function transform to transform the

values.

transform Cloud Code Function. From https://github.com/lupyuen/thethingsio-wifi-geolocation/blob/master/transform.js#L1-L36

7️⃣ Cloud Code Function transform

computes the actual floating-point temperature tmp given the raw

temperature t.

It calls Cloud Code Function

update_thing to update the thing state with the computed

temperature tmp. The transformed key is added to the sensor values to indicate that the

sensor values have been transformed.

This leads to Steps 4️⃣ and 5️⃣

that we have seen earlier. Any dashboards that render the tmp

value will be automatically refreshed.

forward_geolocate is triggered once again, leading to the final

step…

pushSensorData from Cloud Code Trigger forward_geolocate. From https://github.com/lupyuen/thethingsio-wifi-geolocation/blob/master/forward_geolocate.js#L17-L60

8️⃣ forward_geolocate

takes the geolocated and transformed sensor values (latitude, longitude, accuracy, computed

temperature) and transmits them to an external server blue-pill-geolocate.appspot.com via a HTTP POST request.

This step is not needed if you’re not using an external server to share your sensor data publicly.

Details of the external server

setup may be found in gcloud-wifi-geolocation

Note that the nRF24L01 Sensor

Node Address (e.g. B3-B4-B5-B6-F1) is transmitted to

thethings.io as sensor field node. It’s possible to interpret

the node field so that each Sensor Node is represented by a

different Thing in thethings.io. In the update_thing

Cloud Code Function, we may map node to a Thing Token using a

predefined mapping table. If you need more details, drop me a note!

Bootloader Stub

The application for the Sensor Network has grown quite complex, since it contains drivers for both nRF24L01 and ESP8266, as well as the encoding libraries for CoAP, JSON and CBOR message formats.

To squeeze the code into 64 KB of

ROM on Blue Pill, we have switched to a smaller bootloader called

boot_stub.

This bootloader doesn’t do any of the typical Mynewt Bootloader

functions; it simply jumps to the application code.

The bootloader fits in 4 KB of ROM. The rest of the ROM (up to 60 KB) is available for the application.

The Board Support Package for

Blue Pill has been locally patched on your Mynewt build to use the new memory layout: bluepill.ld,

bsp.yml.

The ROM flashing scripts in the scripts

folder have also been updated.

The current application size is

close to 60 KB. If we’re not using the debugger, we may reduce the application size by switching the

build profile from debug to optimized in targets/bluepill_my_sensor/target.yml:

target.build_profile: optimized

What’s Next?

The full power of Apache Mynewt is obvious while we were building the Sensor Network on Blue Pill…

1️⃣ Simultaneously receiving and transmitting sensor data messages

2️⃣ Multitasking of network drivers (nRF24L01 and ESP8266) with interrupts

3️⃣ Built-in CoAP, JSON and CBOR encoding and decoding

4️⃣ Built-in Sensor Framework for multitasking multiple sensors, including Remote Sensors

All this compiled into 60 KB of ROM on Blue Pill!

And we have wrapped all of the above into a Sensor Network Library that’s Network-Agnostic (works on any network) and makes Sensor Network development so simple.

I’m keen to prove that Network-Agnostic IoT is feasible, that we can make the same device code run on any network. Today I have proven this for ESP8266 (WiFi) and nRF24L01 networks, tell me which networks I should tackle next!

[UPDATE] I have ported the code in this article to Rust for a safer, smarter coding experience…

I have added NB-IoT support for the Sensor Network Library here…